Northern California Coast & Redwoods

Northern California Coast & Redwoods

Discover the geologic story that shaped this scenic wonder from Oregon to Fort Bragg.

Geologic Background

The northern California coast has been the site of tectonic plate collisions since over 200 million years ago. During that time, most of Washington, Oregon, and northern California were added to North America. Small continents, volcanic chains, seafloor sediments, and oceanic crust were scraped off the subducting plate and plastered onto North America. Along much of the coast, exotic old subduction zone rocks have been uplifted along the coast.Over time, the crust here is slowly rising. You can see evidence of uplift in the many terraces above current sea level. I'll show you some below.

The sea stacks (the big rocks out in the waves) are made of metamorphic or sedimentary rocks that are simply harder than the rocks around them. Much of this coast is "melange," a mixture of rocks churned together in the subduction zone. Where the melange includes a lot of shale, it erodes away quickly, leaving behind the harder rocks. Wherever you see sea stacks, you're seeing the former extent of the bedrock. Wave erosion has cut it back to today's cliffs, and the process continues.

This trip starts at the Oregon border and progresses southward along U.S. 101, takes a detour up U.S. 199 near Crescent City, through the Redwoods on Avenue of the Giants, southward to Leggett where we join Highway 1, and follow it south to Fort Bragg.

Smith River

This is the north end of a long sand spit that diverts the mouth of the Smith River about 2 miles to the north. The process that moves sand along a coastline is called longshore drift, and here it's predominantly from south to north. You'll see that every river is diverted this way.

See the harbor seals and sea lions basking on the sand?

One of my very favorite swimming holes is at the confluence of the two forks of the Smith River, near Hiouchi up U.S. 199. This spot is famous among geologists because it's an "ophiolite," a complete slice of oceanic lithosphere from seafloor down into mantle. The rocks at this spot are harzburgite, which is oceanic mantle. It's extremely hard and dense, and not very pretty. But it's your chance to stand on Earth's mantle!

Smith River runs so clear and colorful because it lacks sources of mud and shale to dirty the water. You can thank the unique tectonic history here for that.

The gray rocks here are banded mafic gneiss, which formed in the lower oceanic crust. It would have taken an incredibly powerful flood (or several) to transport that big gray gneiss boulder here from miles upstream!

Looking downstream from the Douglas Park bridge toward the confluence. The extensive gravel here with its large rocks indicates a history of powerful floods. More on the floods later.

Take the Douglas Park Road to the Howland Hill Road, which crosses Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park and takes you to Crescent City. The road is narrow and dusty, but is one of California's most scenic drives.

Being in the redwoods is like nothing else on Earth. It's quiet, with sounds muffled by a thick blanket of needles, bark, and ferns. The trees tower so high above you, their tops are usually not visible.

Stop and walk through Stout Grove. A stroll through the redwoods is like a stroll through an older, quieter, more peaceful world.

Redwood burls are a prized northern California product. Tables made of them can sell for several thousand dollars. Their origin isn't quite understood.

You'll see many fallen trees with their giant roots. Redwood roots are shallow and intertwined so that they effectively support each other (as we all should).

While not nearly the largest redwood tree, this one at the group stage is pretty impressive! Redwoods can be up to 36 feet (11 meters) in diameter and over 350 feet tall.

Every time you walk up to one of the fallen giants, your brain will struggle to believe how big it is! I love the deeply grooved bark on this one.

This is the Howland Hill Road. As you can see, it's not wide, nor is it paved. Trailers are not recommended.

Crescent City

We enjoyed the Ocean Life Aquarium in Crescent City. It has some large tanks with local critters, and this "petting zoo" tidepool.

The aquarium had these great before-after photos of Crescent City from its most recent tsunami. It caused around $50 million in damages to the harbor. Crescent City is prone to damage from even far-away tsunami -- like this one all the way from Japan -- because of a huge ridge on the ocean floor (the Mendocino ridge) that seems to divert tsunami toward Crescent City, and the bay's squarish shape that bounces waves right back at the incoming ones.

The biggest tsunami to hit Crescent City so far was from the Good Friday quake near Anchorage, Alaska in 1964. That M9.2 was the second largest quake ever recorded, and it put a wave 7 feet tall into the town.

This Google Earth view shows the extensive jetties that protect the Crescent City harbor from waves and storms. Tsunami can still sweep into the harbor because they are not waves on top of the water, they are compressed pulses from the deep ocean.

This harbor seal was a lot of fun. She could bark like a dog, grunt like a pig, and do several cute gestures. The aquarium is quite small, but kids will love it.

The outer jetty (called Lighthouse Jetty) is impressively tall and long! It was first constructed in 1920, and improved in 1957. In 1986, it was again reinforced with over 700 "doloses," concrete blocks in complex arrangements that help break up waves.

Over by the lighthouse is a good place to explore tidepools. The bedrock here is greywacke, a dark sandstone made of volcanic rock fragments. Greywacke is typical of convergent plate boundaries where a chain of volcanoes formed inland, and supplies the coast with dark sand.

The Battery Point Lighthouse is on an island at high tide, so plan on walking out there at low tide.

The town of Crescent City is on a marine terrace, which is a platform of bedrock eroded flat by waves and then uplifted. There are marine terraces along the entire California coast.

Trees of Mystery

Don't let the hokey name fool you -- this is a wonderful place to visit for anyone who loves the Redwoods! It's also quintessentially American kitsch. It's located along U.S. 101 north of Klamath.

This enormous tree -- which is as big across as your living room -- really puts our place in perspective.

A good illustration that these trees are very old. You can find several slabs with tree ring dates in the Redwoods, some of which show older dates than this.

Fern Canyon

This is a nice diversion off the highway. South of Prairie Creek, look for the sign to Davison Road, Elk Meadows, Gold Bluffs Beach, and Fern Canyon. The road is dirt, so it's quite dusty when dry and sloppy when wet. Cars are just fine when it's dry, but I would not try it in the wet.Fern canyon is a unique box-shaped cut through barely consolidated gravel. The sides are vertical and the bottom is flat, and everything is covered with ferns.

Bring water shoes, because you have to talk through the creek. But it's worth it for the unique scenery.

Back southward on 101, you'll pass the three big Humboldt Lagoons. This one is the craftily named "Big Lagoon." A lagoon is a body of water cut off from the ocean by sand spits or a baymouth bar.

Patricks Point

This scenic state park has some wonderful, easy walking trails. Take the one to "Wedding Rock," shown here.I noticed this landslide scarp in the parking lot above Wedding Rock. There are actually several. The hillside between here and the rock is a landslide complex that is evidently still slipping toward the waves.

Avenue of the Giants -- Humboldt Redwoods -- Eel River

Now we'll skip past Arcata and Eureka (good for lodging and food!) and go right to the heart of the Redwoods. Just south of Scotia and Stafford, take the Avenue of the Giants exit.What can I say about Avenue of the Giants? I rank it in my top three favorite roads, along with the Beartooth Highway and Highway 1 south of Monterey. We drove the entire length, never exceeding 30 mph, just trying to soak it all in.

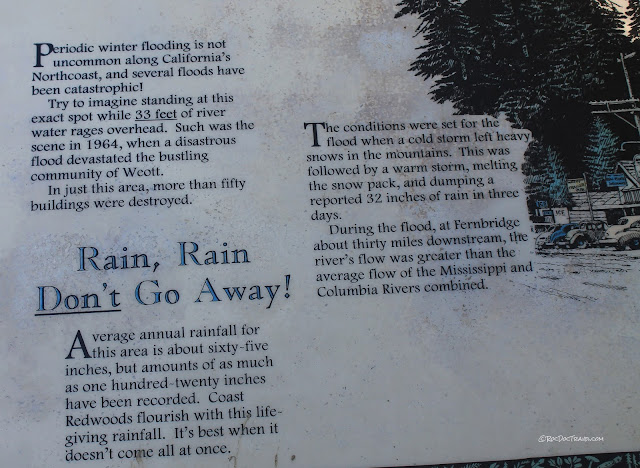

By the road into Founders Grove is this sign for the Christmas Flood of December, 1964. This was the biggest flood northern California seen in centuries. So, the marker is about 16 feet above the ground. The riverbed is 55 feet below the road here. The confluence of the Eel River forks is a few hundred yards downstream. That means the Eel river here was about 71 feet deep and about 1/2 mile wide! More below.

The big gravel bars on the Eel River mark the typical seasonal maximum water level. This was a dry year, so the river was quite below the gravel bars.

This flood marker at the former townsite of Weott shows how unbelievable the December 1964 flood was. It was 33 feet deep at this pole, and the ground I'm standing on is 35 feet above the riverbed. That's a big flood!

These two signs are near the flood marker pole in Weott. Some of the coast ranges got up to 60 inches of rain during this storm!

The statistic that boggles my mind is the flood discharge -- the amount of water flowing by. It was greater than the Mississippi and the Columbia rivers COMBINED!

Fort Bragg Coast - Highway 1

At Leggett, take Highway 1 south. This picture shows where it emerges from the mountains, looking south toward Fort Bragg. The uplifted marine terraces here are hard to miss!Looking north from the same point, you can immediately see why there's no road along the coast north of here.

The marine terraces are underlain by young coastline sediments, mostly sand. Below them are variously folded and tilted older coast sedimentary rocks.

North of Fort Bragg, the coast is nicely rocky and picturesque where the bedrock is the Cretaceous Franciscan melange, the old subduction zone rocks. Harder rocks like chert, sandstone, greenstone, and blueschist make up most of the rocks and sea stacks.

The circled area shows a rare good exposure of the Franciscan melange. The dark material is sheared shale (ocean bottom sediments), and the blocks are metamorphosed ocean crust.

In the cliff you can see three ages of rocks. The oldest rocks of the melange are the dark-colored ones near the bottom. The middle tan rocks are older coastal sedimentary rocks, and the uplifted marine terrace is made of much younger coastal sediments.

I'll end this trip with a picture of my favorite flower -- the California golden poppy. Watch for them in the Spring!

Related Posts

Northern California Coast parts 1, 2, and 3

San Andreas Fault in San Francisco Area