Arches National Park

Arches National Park, Part 1

The Front Half

There's a lot more natural magic to explore at Arches than just the arches!

Interactive Google map

Getting There:

By Air: Moab's Canyonlands Field Airport (CNY) is served by smaller planes operated by United and Sky West airlines. Flights are expensive.

By car / RV: The park is located just outside of Moab, Utah, a touristy town of just over 5000 people. It's on U.S. highway 191, and not near any bigger cities.

Lodging: Moab is well-equipped with motels, lodges, B&B's, Air B&B's, RV parks, campsites, and resorts. You can even do like I do, and take your RV out into the desert somewhere to camp in the silence and darkness!

Seasons: Arches National Park is open all year, although unusual winter storms can close the main road. I recommend spring and fall to avoid the mid-summer crowds (the park can get very crowded at popular times, holidays, and weekends).

Crowds: Avoid mid-May through August! Parking at sites in the park is extremely limited, and becomes impossible when crowded. Here's a quote from a park pamphlet: "Trailhead parking is limited. If parking lots are full, move on and come back later. For the best chance of finding a spot, arrive before 9 am or after 3 pm."

Weather: Arches can be hot in July and August, over 100 F (38 C), but that's not every day. It's in the high desert, so days can be hot while nights are chilly. Brief afternoon thunderstorms are common in summer. Conditions can change dramatically and rapidly. Be sure to check the forecast before setting out on hikes.

Accessibility: You can see a huge number of arches right from your car! Many trails are also wheelchair-accessible, at least for some distance away from parking lots. See the park's website for more detailed information.

Hiking: Arches offers some of the most fascinating hikes you'll ever take! Pass through deeply carved sandstone mazes, walk along red rock spines, and traverse sandy red desert landscapes. You'll find trails suitable for every level of hiker.

In The Area: You'll want to combine this trip with Canyonlands National Park and Dead Horse Point State Park. Other amazing sites include the Colorado River canyon, Castle Valley, the La Sal mountains, and even more distant places like Four Corners, Mesa Verde, and the Grand Canyon.

Off-Road: Moab is a well-known nirvana for all kinds of off-road vehicles, and I highly recommend bringing or renting whatever suits your tastes and abilities! Guided Jeep (and other ORV) tours are available if you don't have your own vehicle -- just do a web search on "Moab Jeep tours."

You'll want to avoid Moab the week(s) of the annual Jeep Safari, usually around Easter (that is, unless you're taking your Jeep!) -- lodging is sold out for miles around, and everything is miserably crowded.

Website: https://www.nps.gov/arch/index.htm

The arches are in the Entrada Sandstone, which is the thick cliff former you see throughout the park. It was laid down as sand dunes in the Jurassic period between 144 and 208 million years ago (precise dating is difficult to impossible in windblown dunes). The thinner layered, darker layer below it is the Carmel Formation, deposited as mud in a shallow sea.

It doesn't.

Arches are collapse features, usually in sandstone (although if you look through my web pages, you'll see some in limestone). When the softer layer below the sandstone gets washed away by rain, it leaves the sandstone hanging. Under its own weight, slabs of sandstone collapse (fall off) along arch-shaped fractures. Here's a picture of a sandstone cliff trying to form an arch, near the park entrance:

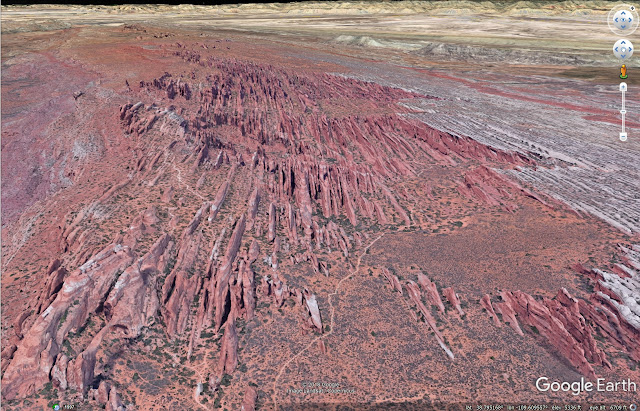

The magic ingredient at Arches National Park is joints (fractures). The sandstone is broken into long, thin ridges or "fins," as you can see in this Google Earth image looking from Sand Dune Arch to past Devil's Garden:

Or this view along the trail past Landscape Arch (visible at lower left):

So when the sandstone is undercut by water erosion, slabs of sandstone fall under their own weight from the arch-shaped fractures. If the fractures break all the way through the ridge, an arch is born!

Travel to Arches National Park

Interactive Google map

Getting There:

By Air: Moab's Canyonlands Field Airport (CNY) is served by smaller planes operated by United and Sky West airlines. Flights are expensive.

By car / RV: The park is located just outside of Moab, Utah, a touristy town of just over 5000 people. It's on U.S. highway 191, and not near any bigger cities.

Lodging: Moab is well-equipped with motels, lodges, B&B's, Air B&B's, RV parks, campsites, and resorts. You can even do like I do, and take your RV out into the desert somewhere to camp in the silence and darkness!

Seasons: Arches National Park is open all year, although unusual winter storms can close the main road. I recommend spring and fall to avoid the mid-summer crowds (the park can get very crowded at popular times, holidays, and weekends).

Crowds: Avoid mid-May through August! Parking at sites in the park is extremely limited, and becomes impossible when crowded. Here's a quote from a park pamphlet: "Trailhead parking is limited. If parking lots are full, move on and come back later. For the best chance of finding a spot, arrive before 9 am or after 3 pm."

Overflow summer parking at Devil's Garden (NPS)

Weather: Arches can be hot in July and August, over 100 F (38 C), but that's not every day. It's in the high desert, so days can be hot while nights are chilly. Brief afternoon thunderstorms are common in summer. Conditions can change dramatically and rapidly. Be sure to check the forecast before setting out on hikes.

Accessibility: You can see a huge number of arches right from your car! Many trails are also wheelchair-accessible, at least for some distance away from parking lots. See the park's website for more detailed information.

Hiking: Arches offers some of the most fascinating hikes you'll ever take! Pass through deeply carved sandstone mazes, walk along red rock spines, and traverse sandy red desert landscapes. You'll find trails suitable for every level of hiker.

In The Area: You'll want to combine this trip with Canyonlands National Park and Dead Horse Point State Park. Other amazing sites include the Colorado River canyon, Castle Valley, the La Sal mountains, and even more distant places like Four Corners, Mesa Verde, and the Grand Canyon.

Off-Road: Moab is a well-known nirvana for all kinds of off-road vehicles, and I highly recommend bringing or renting whatever suits your tastes and abilities! Guided Jeep (and other ORV) tours are available if you don't have your own vehicle -- just do a web search on "Moab Jeep tours."

You'll want to avoid Moab the week(s) of the annual Jeep Safari, usually around Easter (that is, unless you're taking your Jeep!) -- lodging is sold out for miles around, and everything is miserably crowded.

Website: https://www.nps.gov/arch/index.htm

A Basic Outline of Arches Geology

The Rock Layers

A note about the word "formation": In geological science, a "formation" is a rock body defined by its rock type. In contrast, informal use of "formation" includes things like erosional remnants, arches, towers, buttes, and so forth. I will use the formal definition that refers to rock layers.

Rock formations (stratigraphy) in the Arches area. (National Park Service)

The arches are in the Entrada Sandstone, which is the thick cliff former you see throughout the park. It was laid down as sand dunes in the Jurassic period between 144 and 208 million years ago (precise dating is difficult to impossible in windblown dunes). The thinner layered, darker layer below it is the Carmel Formation, deposited as mud in a shallow sea.

How Arches Really Form

I remember hearing in my junior high science class that arches are formed "by wind and water." And that falsehood is still repeated today! Think about it: how many blinding sand storms have you ever heard about in Arches National Park? None, right? So how would wind form arches?It doesn't.

Arches are collapse features, usually in sandstone (although if you look through my web pages, you'll see some in limestone). When the softer layer below the sandstone gets washed away by rain, it leaves the sandstone hanging. Under its own weight, slabs of sandstone collapse (fall off) along arch-shaped fractures. Here's a picture of a sandstone cliff trying to form an arch, near the park entrance:

The magic ingredient at Arches National Park is joints (fractures). The sandstone is broken into long, thin ridges or "fins," as you can see in this Google Earth image looking from Sand Dune Arch to past Devil's Garden:

Or this view along the trail past Landscape Arch (visible at lower left):

So when the sandstone is undercut by water erosion, slabs of sandstone fall under their own weight from the arch-shaped fractures. If the fractures break all the way through the ridge, an arch is born!

Geology of Arches National Park

Let's work our way from the entrance into the park (that's south to north).

This panorama looks down onto the entrance, with U.S. highway 191 in the foreground. The Moab valley was formed by erosion along a fault, which dropped down the near side and lifted up the far side. Faults tend to be easily eroded because they crush and fracture the rocks, giving water and ice plenty of foot-holds to do their work of removing rock.

This park sign shows where the Moab fault is.

"Park Avenue" is a great place for an easy scenic hike. It's a short canyon with vertical sides that resemble skyscrapers.

Park Avenue gives you a good look at the Carmel Formation (the lower, thin-layered cliffs) below the massive Entrada.

See the curved fractures in the center of this photo? Those are snapshots of fracture growth called "arrest lines." As a slab broke off this face, the fracture grew from top toward the bottom. The evidence is the curvature of these arrest lines. Look around -- you'll see them all over the park!

Park Avenue. You may recognize this from the opening credits of the 1989 film "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom."

When I'm visiting a scenic place and clouds appear, I think "hooray!" They make your photos much more interesting than a clear blue sky. Those are the La Sal Mountains behind the clouds.

The Courthouse, sitting on a layered base of Carmel Formation.

Three Gossips also appear in the Indiana Jones film.

Here's an end-on view of the three gossips. One gossip?

The road in Arches is in the best possible location! It takes you right to and through the best features, like this passage between The Courthouse (left) and the Three Gossips (center).

Sheep Rock. See the tiny window up high?

The road crosses Courthouse Wash with a good view of The Tower of Babel (left center).

The cliffs north of the Petrified Dunes viewpoint show the Navajo Sandstone at bottom, the Carmel in the middle, and the thick Entrada in the cliffs. Notice how the Carmel is deformed -- it's softer than the other layers, and the weight of the Entrada sandstone has folded it.

A fracture cuts this huge cliff in the center of the photo. It's one of the many joints that divide the sandstone into long, narrow fins.

The "petrified dunes" are the Navajo Sandstone. This is the same sandstone that forms the beautiful cliffs at Zion National Park. It represents the largest preserved dune field in the geologic record. The La Sal mountains are in the background.

Looking toward the aptly named "The Windows" area.

Balanced Rock is an eroded remnant of the lower Entrada Sandstone sitting on the layered Carmel Formation. Looking carefully, you'll see that this is a narrow fin just like the arches, but this one has been eroded through. It also appears in the opening credits of "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom."

--> Turn onto The Windows road near Balanced Rock.

Towers like these are erosional remnants of the sandstone "fins" formed by erosion along joints. The reason for so many towers here is the higher uplift and consequent deeper erosion on this uplift. Erosion has exposed the hard Navajo Sandstone (the light-colored sandstone) and the easily eroded Carmel (the lower parts of the towers). Intact remnants of the hard Entrada on top protect the lower Carmel from erosion, like a hard hat. Where the Carmel erodes enough, the Entrada falls.

More towers with Entrada caps protecting Carmel towers from erosion.

Climbers on Owl Rock near the Garden of Eden.

Climbers on Owl Rock near the Garden of Eden.Here's a rare cap of Carmel on top of the cross-bedded dunes of the Navajo.

By the "Cove of Caves." The tops of the arches are in Entrada, but the lower, redder layered cliffs are Carmel.

Past the end of the road, you can see North Window and Turret Arch.

The view back to the west is like nothing else on Earth!

...and Fiery Furnace.

See Part 2 for the "back half" of Arches, including Delicate Arch, Fiery Furnace, and Landscape Arch!

Arches National Park, Part 2

Grand Canyon

Dinosaur National Monument

Canyonlands National Park

Zion National Park