Dinosaur National Monument, Utah

Dinosaur National Monument, Utah

Discover this truly unique, phenomenal geologic site!

Why Visit Dinosaur National Monument?

At Dinosaur, you'll see dinosaur bones in-place where they died -- and not just one or two, but dozens in one place!

The Monument has of some of the West's best scenery -- a rugged protected dome-shaped mountain of colorful bedrock exposed in slopes and canyons. But for visitors, the highlight is the quarry. Many famous dinosaurs now displayed in big museums came from this quarry, and you can see how & where they were originally discovered.

For geologists and fans of Earth, Dinosaur has unmatched displays of rock strata, folding, differential erosion, and an antecedent stream (the Green River, explained below). You can go as deep into Earth science here as you want!

Travel to Dinosaur National Monument

It's located outside of Vernal, Utah near the Colorado border. It's on U.S. 40 between Denver and Salt Lake City.Interactive Google Map of Dinosaur National Monument.

Travel: This is a driving destination, and easy to find. The closest airports aren't close -- Grand Junction, Colorado; Denver; Salt Lake City.

Lodging: Vernal has a lot of good lodging options. The Monument has a few campgrounds that fill up quickly in June to early September.

Seasons: Pleasantly warm in summer, very cold in winter, the park is open all year. I recommend mid-May to mid-September. High elevation roads in the back country are closed in winter.

Accessibility: The quarry and paved roads are accessible to everyone and every type of vehicle!

Things To Do: There's a lot more than just the visitor center and quarry -- auto tour roads, and outstanding hiking, backpacking, camping, river rafting, and stargazing.

Website: https://www.nps.gov/dino/index.htm

Geology of Dinosaur National Monument

The park centers around its folded Cretaceous and Jurassic dinosaur-laden rock layers, but you'll see colorful younger and older layers as well.

The first thing you see is the tilted sandstone layers at the front of the park. They're the south side of a long anticline (a convex-upward fold). Tilted sandstone layers often erode into "flatirons," triangular slabs that point upward. They're triangular because rivers and streams cut inverted triangular canyons through them, leaving flatirons between the canyons.

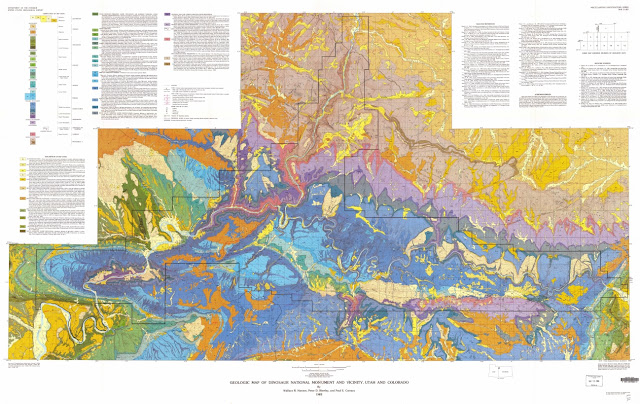

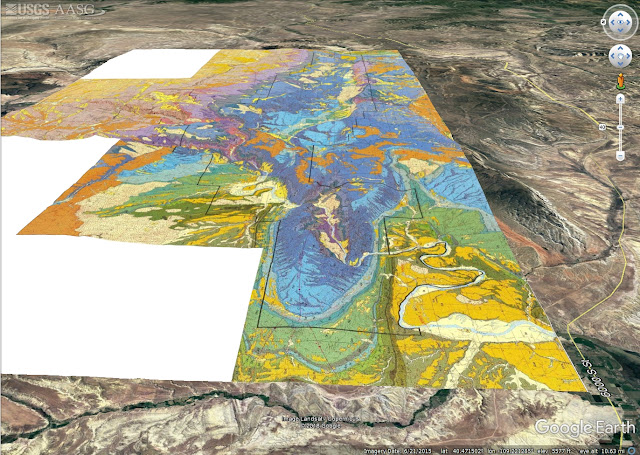

One of the cool things the U.S. Geological Survey does is provide draped images of its geologic maps for Google Earth. This is also available at the link above. It shows how big the Monument is -- the anticline where the quarry and visitor center are is in the lower foreground, but the Monument extends far across the domal mountain.

Here's the same view without the geologic map.

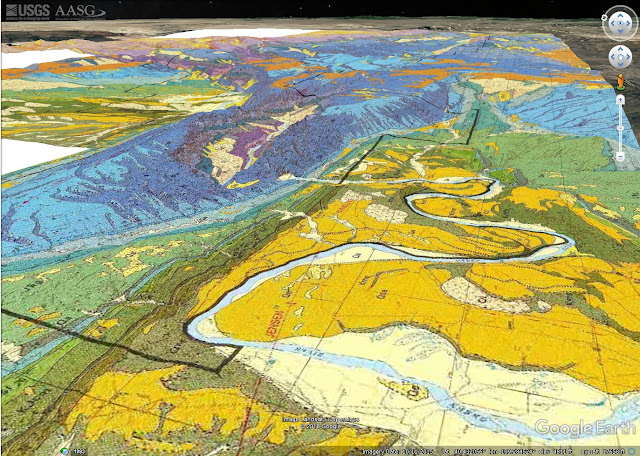

In this closer view, you can see the south flank of the anticline and the rows of Cretaceous & Jurassic rock layers (the symbol for Cretaceous is K; shades of green). The visitor center and quarry are where the Green River is closest to the green rows of tilted rock layers.

Here's the same view without the geologic map.

This amazing chart from the Utah Geological Survey shows where the various dinosaurs are found in the rock layers. Visit geology.utah.gov for more.

Dinosaur Visitor Center and Quarry

Stop first at the Visitor Center to get oriented. It has a good overview of the geology and all the things to do.

Just up the road into the hills from the Visitor Center, the quarry is housed under a big glass box to protect it and provide you with a comfortable and well-organized visit.

A lot of bones have been removed from this quarry and taken to museums around the world, but there are still plenty in place! The sandstone is hard, and must be chipped away carefully to uncover the bones. The brushing you see in movies and documentaries happens only after the rock has been chipped away already. It's mostly a process of hammering and scraping. Larger bones are a bit harder than the sandstone -- but not much -- and it takes very careful work not to damage them.

Picture how these animals died. They were giant, hungry animals that spent most of their time where there was plenty of food -- in the jungle, and near water. Whether they died by old age, disease, starvation, or fights, the ones that got preserved fell into the river or were soon buried by flooding. Their bodies were jumbled on top of each other in all kinds of orientations. Some bodies weren't even intact, but remarkably, many were. And keep Time in mind -- what you're seeing is layer after layer laid down over huge spans of time. The Morrison Formation was laid down from about 155 to 149 million years ago, so these piles of bones are a long record, not a quick snapshot.

The quarry has this excellent illustration of what the landscape looked like when these dinos were stomping around. The Jurassic in Utah was a warm, wet, lush landscape with plenty of food for both the plant-eaters and meat-eaters. (National Park Service diagram)

Walk along the quarry, and pay attention to the variety of bones and body parts in the rock. Here's a recognizable spinal column and some big shoulder blades.

Dinophiles of all ages will have a good challenge just naming all the beasts found here, and an even bigger challenge identifying them by just a few of their bones.

It's surprising to me that the park does not provide an index map to the bones in the quarry. Some signs tell you about particularly interesting clusters of bones, but this publication by the Carnegie Institute is the closest I can find to a bone map. And it's information is buried in the article's text. Link: https://doi.org/10.2992/007.081.0301

Those leg bones are 5 to 7 feet long!

Here's another spine-tingling view.

The quarry has been developed and the structure built over several decades.

Some of the famous dinosaurs taken from the DNM quarry.

One of Dinosaur Monument's reconstructed dinosaurs (National Park Service photo).

Interestingly, there's no master index map to the quarry so you can name all the bones and what animals they came from. A few of the signs at the quarry help, but they don't label everything.

Like animals today, these dinosaurs' remains were preserved where they were buried quickly before organisms could eat them away. That often means rivers. These piles of carcasses accumulated in a river, where mud buried them and sealed them from oxygen and organisms that could have destroyed them.

What animals would be most likely to be preserved if they died today? Well, they would have to die somewhere their bodies could be quickly buried, like a river or even a lake, or perhaps the ocean bottom, and only then if a significant supply of mud were settling over them. Not only that -- the groundwater would have to slowly replace bones with minerals, and bones could never be eroded out for millions of years. And in the case of the bones at Dinosaur Monument, they were eventually uplifted and eroded out to where we could find them! How many animals we're familiar with could that happen to?

A deer, bear, coyote, or rabbit would have to fall into a river when it died, and not only that, the river would have to be accumulating mud from that moment onward. And then all the fossilization and preservation would have to take place. It's quite remarkable that we have as many fossils as we do! It takes a specific and unusual set of circumstances to all come together to preserve bones.

And that's what makes Dinosaur Monument so remarkable! All the factors that came together to create and preserve these bones are unfathomably rare.

A future Roc Doc studies the sign, discovering the secrets dug out of this mountainside.

The west end of the quarry.

Yes, the Monument does have some reconstructed dinosaurs like this Camarasaurus.

How many spinal columns, scapulas, and leg bones do you see here? The completeness of these dinosaurs' remains is remarkable.

You can get up close and personal with some of the bones.

When you see a complete skull like this, doesn't the little kid in you get excited? This is an Allosaurus, a kind of mini-T-Rex. They grew up to 32 feet long, had longer arms than a T-Rex, and had three "fingers" instead of two.

Dinosaur Monument Mountains

Looking east from the quarry parking lot, you see the strata standing on-end. The quarry layer is the ledge-forming brown sandstone to right of center. Below it (to the left) is the older mudstones of the Morrison Formation, and above it is the Cedar Mountain Formation.Take the main Park road eastward toward the mountains. You'll see the light-colored Weber Sandstone forming the biggest cliffs and best preserved anticline. It's Pennsylvanian to earliest Permian in age, older than the dinosaurs. So just think -- while the dinosaurs were walking around this area, the rock layers in this view were deep below their feet!

You'll get excellent eastward views of the folded layers sloping down under the valley.

When you look northward into the fold, you see the strata dipping toward you with V-shaped notches where streams have cut through them. The big notch to right of center is the Green River's canyon.

Split Mountain

View into the "Split Mountain" canyon of the Green River, with Cottonwood Wash campground in the foreground. The big cliffs are the Weber Sandstone, fossil sand dunes.What most visitors miss: The Green River cuts across this anticline -- think about that! How could a river flow INTO a high area? It can't! So what happened here? The answer is stupidly simple -- the river (or a river) was already flowing across this area when the fold formed. In the right climate, rivers can erode downward faster than most tectonics can lift bedrock upward. And so the Green River's course is older than the fold, which itself is between 70 and 45 million years old. It's called an antecedent or superposed stream.

A lot of geology field trips come to see this! We're looking just to the right of the previous picture (Cottonwood Wash campground in the foreground). The strata are here, in order from left to right, the light-colored Weber Sandstone (sand dunes), yellow and red Park City Formation (coastal and marine deposits), red Triassic Chinle Formation (river and stream sediments), light brown Triassic - Jurassic Glen Canyon Formation (sand dunes), and the dark red Carmel Formation (coastal sediments).

A closer look up the canyon.

Now drive eastward toward Hog Canyon. You'll cross the Green River and drive past some gorgeous farms. Hog Canyon is one of the deep cuts in the anticline.

Hog Canyon

Hog Canyon is a good side-trip to get out and hike a little. It's a deep, steep canyon eroded into the dipping rock layers, and so give you a good look at the rock. It's a box (dead-end) canyon.The narrow opening invites exploration. You'll see Josie Morris's cabin at the mouth. She fenced off this box canyon to keep animals. I wonder what kind?

The cement that holds the sand grains together isn't uniform. Along this layer, water dripping down the cliff face has dissolved the cement in the weakest spots, creating these micro-caves. The technical term is "solution cavities." You can also see the cross-bedding formed when these were sand dunes.

The ridges around Dinosaur are some of the best-exposed, most photogenic folds in the region.

B.S. -- Common Misconceptions

Dinosaurs didn't live in deserts. Disney did irreparable harm when they depicted dinosaurs wandering through deserts in "Fantasia." Like animals today, they lived where there was plenty of food and water. That means forests, jungles, and swamps. We find bones in today's deserts simply because that's where erosion doesn't remove the rocks entirely and we can actually see the bedrock.

Dinosaurs were real and old. Despite the contortions some use to fit dinosaurs into preconceived notions of a young earth or Noah's ark, they really did live millions of years ago while the continents were together as "Pangea." The evidence is irrefutable and abundant. A little research into credible science will convince you.

M.S. -- More Science

The Utah Geological Survey has a lot of good information on dinosaurs, the rock strata, and geologic history of this area! www.geology.utah.gov

Ph.D. -- Piled Hip-Deep

Geologic Map: here

Scientific Papers on the Dinosaur Quarry:

Deposition of the bones: https://geobookstore.uwyo.edu/rmg Rocky Mountain Geology, Volume 53 number 2.

Access scientific journals through your local or university library.