Grand Canyon Rafting - part 4

Grand Canyon Rafting - part 4

Havasu Creek to Vulcan's Throne

Landslides and Lava Flows

See part 1 for logistics details and helpful information.

The Western Grand Canyon

For a long distance west of Havasu Creek, the river is in the lower Paleozoic sedimentary rock layers -- the Tapeats and Muav. The Muav Limestone formed in shallow ocean waters near shore, and it contains limestone, siltstone, and shale. It can be quite colorful!Here's a review of the Grand Canyon rock layers. Thanks, USGS! See my descriptions of the layers here: click here.

You can expect to encounter bighorn sheep along the river. We saw dozens on our trip! River guides are very good about pausing to get close to them.

The section of the canyon where the river is in the Muav is quite narrow and steep. And as a geologist, it frightened me! It's full of slip planes that indicate the cliffs are unstable and falling apart. Old landslides are all over the place, but the ones that are made of solid bedrock layers sitting on top of bedrock layers are not that obvious. A big landslide blocking the river here would come as no surprise to me!

Here are some good towers in the Redwall Limestone up high. The river is in the Muav.

The Muav Limestone is 165 million years older than the Redwall Limestone above it. That means the boundary between them was the ocean bottom for much of that time. A lot of sediment may have been deposited on top of the Muav during that time, but we have no way of knowing. All we know is in some places, erosion cut some broad, shallow channels into the Muav and deposited sediments called the Temple Butte Limestone (see part 1). Those channels are now between the Muav and Redwall. Here in the western canyon, the Temple Butte is not present and the boundary is parallel to the layers above and below, so it gets the special name of "disconformity" to distinguish it from other kinds of unconformities. But try to imagine what this surface represents -- 165 million years of the rock record missing!

Surprise Valley Landslide

The Surprise Valley landslide dammed the Colorado River about 90,000 years ago and changed the river's course. Although the exact cause is not clear, it may have been caused by abundant groundwater (and springs) that saturated the slippery, soft shales in the Muav Limestone.

The lumpy slope is spring deposits, which are common throughout the canyon below the Redwall Limestone. The thin layers are lower left are a good exposure of the Muav.

The river continues through the Muav for many miles. And that's a good thing because its layers are colorful and geologically fascinating. In them, you can see the results of slight fluctuations in sea level and sediment input -- generally, deeper water formed limestone, while shallower water formed shale and siltstone.

Uinkaret Volcanic Field

This black basalt tower appears unexpectedly. As you follow the river westward, you're approaching the large, young Uinkaret volcanic field. This tower is part of a dike injected into the sedimentary rocks, and later eroded out by the river.The fracture pattern in the basalt plug formed when the lava cooled, solidified, and shrank. In centuries past, higher river levels polished this rock 20-30 feet above current river level (up near the high bushes).

The darkest rocks in this part of the canyon are basalt of the Uinkaret volcanic field. The oldest lava flows are about 3.6 million years old at Mount Trumbell north of the canyon, but most of the lava flows are 600,000 to 500,000 years old. A few are much younger.

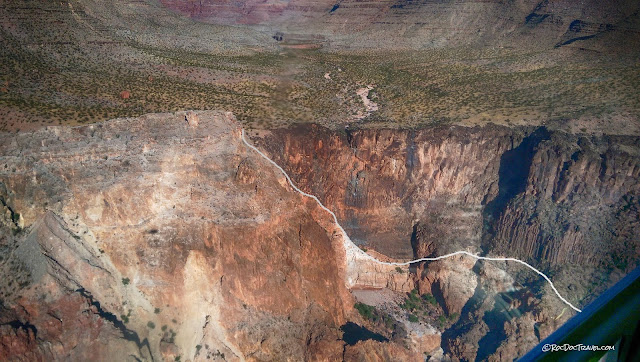

Here's an aerial view of the volcanic field. The marked hill on the right is the 700 foot tall cinder cone called Vulcan's Throne, one of the canyon's most spectacular features. I'll have that in an upcoming post. Google Earth view.

Lava flows dammed the Colorado River many times between about 750,000 and about 100,000 years ago. Remnants of the dams are all over the cliffs in this part of the canyon -- the dark patches of rock up on the canyon walls.

These are the famous Lava Falls rapids, looking upstream. Our big motorized rafts were able to do these rapids twice by motoring up the right side (in this view). Your experience may vary because of varying water levels. The rapids were formed by debris flows out of Prospect Canyon. You can watch a slow-motion video of a big raft going through these rapids here. Location: 36.197836, -113.082967

This spring was a refreshing surprise. It's just below the rapids, and is called Warm Springs.

Basalt lava flows form these fantastic "cooling joints" when they solidify because lava shrinks when it solidifies. Their patterns are controlled by temperature gradients in the lava, and so are affected by things like groundwater, surface water, and topography. These jointed blocks have tumbled down from above. Here, too, you can see that previous river levels were much higher than today because of modern water use, river management, and variations in climate.

Here's a good view of one of the lava falls. Imagine when this lava was pouring over the cliffs! It would have created fantastic steam explosions when it hit the river.

Here you can see basalt remnants and the gravel and slope deposits below them that the basalt protected from erosion.

When these lava flows poured over the cliffs, they filled the canyon and dammed the river. This happened dozens of times, and each time, the river over-topped the dam and eroded it out relatively quickly (what's a few centuries or millennia to the earth?). Wonderful cooling joints here.

The cooling joint patterns in the lava dams are beautiful and complex. They were shaped by temperature gradients, including the effects of the river water.

This place is called Lava Falls for obvious reasons. It's a tremendous amount of basalt that flowed over the cliffs and dammed the river. The volcanic vent is north of the inner gorge.

The lava poured over whatever was on the ground surface and formed a hard cap that has preserved things below from erosion. Here, you can see gravel and blocks of basalt that were in the river or on the slopes nearby when the lava arrived.

These layers of gravel and basalt record the repeated periods of lava flows and longer periods of erosion in-between.

Looking back upstream at a massive lava dam. Try to picture this filling the canyon all the way across -- it was an impressive dam that formed an equally impressive lake! The biggest lava-dammed lakes extended all the way up the river through southern Utah to western Colorado. The evidence is lakeshore sediments perched up high on the cliffs.

Maybe it's a little easier to see the basalt when it's outlined. Picture these remnants all connected, and you can imagine the resulting dam and lake.

This is a thick, continuous lava flow that would have been massively impressive when it was flowing! This is just a small remnant of a once-extensive flow. Because it couldn't easily erode through it, the river flowed southward around this basalt.

Try to spot the basalt remnants perched on the cliffs. The amazing thing to remember is that these were once parts of deep, continuous lava flows that filled the canyon.

The dark rock is a remnant of a lava flow.

The black rocks are remnants of one of the big lava dams.

Here's another preserved section of a lava dam.

Yet another lava dam on the right.

This lava remnant shows the slope of how the lava flowed down the canyon. In the distance is a narrow lava fall.

The reddish and grayish rocks are sedimentary, and the black are basalt lava that covered them. The basalt here is made of many lava flows stacked on top of each other.

Lava pouring over the Grand Canyon cliffs would have been one of the world's most spectacular sights!

Look how lava poured through this narrow notch.

A look back upstream at the narrow lava fall.

For several miles, you'll pass various lava falls and remnants. In the distance is yet another.

These are beautiful cooling joints! They generally form perpendicular to cool surfaces like the air, ground, or water. You can see them in nearly every volcanic field -- Idaho's Snake River Plain, the Columbia Plateau of eastern Washington, the Columbia River Gorge, and throughout the Cascades. Some of the most spectacular are in Devil's Postpile National Monument. See more in my other field trip posts.

More lava falls.

Here's an aerial view looking northeastward at the west end of your rafting trip (if you use Hatch Expeditions) and the west end of the volcanic field. Google Earth view.

Helicopter Flight

Your raft trip will probably end with a helicopter flight out of the canyon. It's one of the most spectacular parts of the whole trip!We camped our last night on this nice little beach at Whitmore Wash (location:36.143459, -113.200728 ). You can see that the raft's outriggers have been deflated and packed aboard. After the helicopter meets you, the river guides have another day-long trip down to Pearce Ferry, where the rafts can be loaded onto trailers for the day-long haul back to Lee's Ferry. I was glad to miss that part of the trip!

Looking downstream as the helicopter flies northward, you can see the flatish areas created by lava flows filling the side canyons. The river has sure removed a lot of material!

The line is the base of a lava flow that filled a canyon.

Remnants of some of the younger cinder cones are still visible just north of the canyon's inner gorge.

Aerial Views

Lava flows underlie this valley. Current streams are trying to erode new canyons into it.Uinkaret lava flows pour over the sedimentary cliffs.

Eroded cinder cones and lava flows of the Uinkaret volcanic field.

This is the youngest lava flow in the field, which occurred between 1000 and 1200 A.D.

More of the volcanic field, looking south toward the Grand Canyon.

Here's a look at the biggest side-canyon in the Grand Canyon, formed by Kanab Creek. That's the Grand Canyon in the distance. Once a creek meets the Colorado River, it is able to erode its entire streambed down to the Colorado's elevation. The process is called "headward erosion," and it takes place as a series of rapids and waterfalls migrating upstream.

______________________________________________________________

Well, that's the end of the trip! I hope you're able to take this fantastic rafting trip through one of nature's most wondrous wonders!

M.S. -- More Science:

This is a classic article by one of my old Professors:

W.K. Hamblin, 1994, Late Cenozoic lava dams in the western Grand Canyon: Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society of America Memoir 183, 139 p.

You'll need a subscription or pay a fee to access this paper, but you'll find lots of web articles derived from it. Just search for "Grand Canyon lava" and you'll find a lot to read.

A very good summary with pictures of the Uinkaret volcanic field, taken from Kenneth Hamblin's classic paper:

http://volcano.oregonstate.edu/oldroot/volcanoes/volc_images/north_america/uinkaret.html

Info about the lava dams: U.C. Davis

Geology of the Toroweap Overlook area (Tuweap) by USGS:

https://www.nps.gov/grca/planyourvisit/upload/Tuweep-Geology.pdf

The geology of Lava Falls rapids by USGS:

https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1996/ofr96-460/pdf/ofr96-460.pdf