Yellowstone East

Yellowstone Lake to Cody, Wyoming

See some of the region's best scenery and geology!Interactive Google map.

Route: Start at Fishing Bridge at the north end of Yellowstone Lake, and take the East Entrance Road toward Cody. It's US highway 14 all the way. This can be a loop with with the fantastic Beartooth Highway (see other posts here and here).

Lodging: Stay inside Yellowstone or at Cody - there are many choices!

Logistics: There are only a couple of places you can get food between Fishing Bridge and Cody, so it's best to bring lunch and water/drinks.

Considerations: The road does have long inclines, so heavy vehicles should be in good shape (brakes and radiator, especially).

Seasons: This road is closed in winter, open only to snow machines (highly recommended!)

Yellowstone Lake

Yellowstone Lake occupies a broad low area inside the Yellowstone caldera. In fact, the current center of the "hot spot" of hot rock rising from the mantle is at Fishing Bridge at the north end of the lake. It's a broad, beautiful, cold, and wild lake! And did you know its elevation is 7795 feet (2376 m)? Count on cold nights and mornings, even in mid-summer.Looking northward at the NW corner of the lake. Motorized boating is allowed on the lake by permit. You can find more information at the park's website here.

Looking south. Much of the sand along the western shore is obsidian and rhyolite - the black stuff is obsidian.

When I was a Boy Scout, another troop in our town (Albuquerque) had a terrible tragedy while canoeing on Yellowstone Lake. A fierce thunderstorm arose suddenly, which is a common occurrence, and created 6 foot waves that swamped all their boats while they were far from shore. Two of the boys and two of their leaders drowned in the icy water. With heroic effort, one of the boys made it to shore and ran 17 miles to summon help. At one point, he was treed by a bear for an hour! You can read more of the story at the Chicago Tribune.

Northward view toward Lake Yellowstone Hotel area.

Fishing Bridge is the outlet of Yellowstone Lake. It empties via the Yellowstone River down to the Missouri, and on to the Mississippi and Gulf of Mexico. This is also the center of the hot spot! Study of seismic waves show that the plume of hot, soft rock is centered here. There is magma about 10,000 feet below the ground surface.

The east side of the lake takes on a different character than the west side. The east shore is rockier and steeper where the lake is nuzzled up against the caldera's eastern side.

Take the time to use the pull-outs along the lake's eastern shore - the views and peaceful scenery are worth it.

There is a hot spring at Steamboat Point (see the steam?) along the road. What you can't see are the many hot springs under the lake! There are hot springs above the road at Sedge Beach as well.

Looking west across the lake. Because it's in the caldera, Yellowstone Lake is subject to occasional uplifts and subsidence as the volcano expands and contracts. In some years, the caldera floor can rise or subside as much as 4 feet! The lake's shorelines have varied over the years because of this dynamic landscape.

East Entrance Road

The East Entrance Road climbs out of the Yellowstone caldera into high mountain country full of lakes and snow drifts.

The East Entrance Road takes you through an extensive area that burned in 2003. It forms its own kind of melancholy beauty that reminds us how fragile the park can be. You can see a map of past fires in Yellowstone here.

Sylvan Lake is one of the park's scenic highlights. Its high mountain setting below Top Notch Peak is unmatched in the park. It occupies a spot left low by glaciers long ago.

At 8524 feet (2598 m), it's easy to see why Sylvan Pass is closed to vehicles in the winter. The long talus slopes are evidence that freeze/thaw works most of the year up here, breaking the volcanic bedrock into pieces.

It's a surprisingly long road down from Sylvan Pass to the Yellowstone east gate. Along the way you'll make the transition from mostly light-colored hot spot volcanic rocks to much older dark-colored volcanic rocks of the Absaroka volcanic field.

Absaroka Volcanic Field

A dike (the vertical rock slab) cuts through volcanic conglomerates and lava flows. The brown rocks you'll drive through most of the way from Yellowstone to Cody are the Absaroka volcanic field, one of North America's largest. It formed over a long time, from 49 to 44 million years ago (the Eocene period), a time of tremendous geologic turmoil in the western U.S. Imagine a cluster of giant volcanic cones about 10 miles north of highway 14. They were probably as high as Rainier, or higher. Now imagine them in a wet, tropical climate, and you have an idea of the complex pile of lava flows, flood deposits, pyroclastic flows, and avalanches you're driving through. Look closely, and you'll see that at least half of the rock layers down the canyon are conglomerate - flood deposits of volcanic gravel and boulders.

Dikes like this were the magma feeders to the volcanoes above. Magma makes its way up through the crust through fractures. When the magma stops moving and hardens, it forms dikes like this one. Notice in this canyon how many of the dikes cut through conglomerates! That's remarkable because the conglomerates formed on the earth's surface. They must have been buried pretty deep for magma to fracture them and flow up toward the surface!

The vertical spine on this mountainside is another dike that fed the volcanoes above.

These spectacular cliffs are volcanic conglomerate, flood deposits off the high slopes of the volcanoes in the tropical Eocene climate.

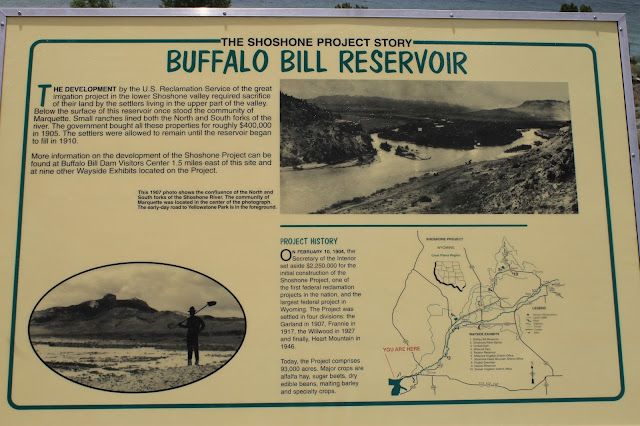

Buffalo Bill Reservoir

Buffalo Bill Reservoir is surrounded by spectacular geology! Rattlesnake Mountain, shown here, is a giant fold that formed just before the Absaroka volcanics. You'll drive right through it on the way to Cody. See my field trip to the Cody area for more details.

Sheep Mountain on the southwest side of the reservoir is capped by one of Earth's biggest landslides, the Heart Mountain detachment. The landslide extends all the way northward to the Beartooth Mountains. See my field trip to the Cody area for more details.

A view westward along the reservoir up the Shoshone River valley. The Heart Mountain landslide is the cliffs. The lower slopes are sandy, shaley valley fill that the landslide rode over.

A view westward from Buffalo Bill dam across the reservoir.

View down the Shoshone canyon from atop the Buffalo Bill dam. Be sure to stop at the excellent visitor center!

Highway 14 passes through the Rattlesnake Mountain fold! On the west end, look for the steeply tilted rocks. On the east end by Cody, look at how the same rocks are gently tilted toward the east.

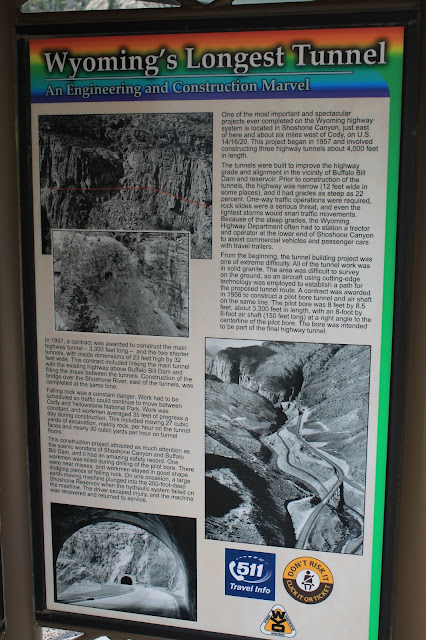

The west mouth of the tunnel is in Archean granite, some of the oldest rocks in the U.S. at about 3.5 billion years.

Cody, Wyoming - Buffalo Bill Center of the West

It's remarkable that a world-class museum is located out here in the wilds of Wyoming! DO NOT MISS the Buffalo Bill Center! The story of Buffalo Bill itself is iconic and historic, but the museum also has art and artifacts from the Yellowstone region and around the west. I enjoyed seeing the century-old film of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show - what a grand and exciting production it was! The Center is well worth the admission price.

Related Posts: Find the Yellowstone and Wyoming labels on the upper right side of this page. You can hardly go on any road in this region without discovering fantastic geology, scenery, and history!

B.S. - Common Misconceptions

Myth: Yellowstone eruptions are always catastrophic.

Reality: 99% of Yellowstone's eruptions have been local lava flows or relatively small eruptions. Keep in mind that Hollywood (including Discover Channel and BBC) need to exaggerate things to increase viewership. Reality is much less exciting.

Myth: A super-eruption could sneak up on us and wipe out all of us.

Reality: Super-eruptions are so rare that none comparable to Yellowstone's big eruptions have happened in tens of thousands of years. We've gotten good at predicting eruptions, and would have several weeks to several months' warning before any eruption, big or small.

M.S. - More Science

Geologic map of Yellowstone at USGS.gov

Geologic map of the Cody, Wyoming area at USGS.gov

PhD - Piled Hip-Deep

All about the Absaroka volcanic field at USGS.gov

B.S. - Common Misconceptions

Myth: Yellowstone eruptions are always catastrophic.

Reality: 99% of Yellowstone's eruptions have been local lava flows or relatively small eruptions. Keep in mind that Hollywood (including Discover Channel and BBC) need to exaggerate things to increase viewership. Reality is much less exciting.

Myth: A super-eruption could sneak up on us and wipe out all of us.

Reality: Super-eruptions are so rare that none comparable to Yellowstone's big eruptions have happened in tens of thousands of years. We've gotten good at predicting eruptions, and would have several weeks to several months' warning before any eruption, big or small.

M.S. - More Science

Geologic map of Yellowstone at USGS.gov

Geologic map of the Cody, Wyoming area at USGS.gov

PhD - Piled Hip-Deep

All about the Absaroka volcanic field at USGS.gov